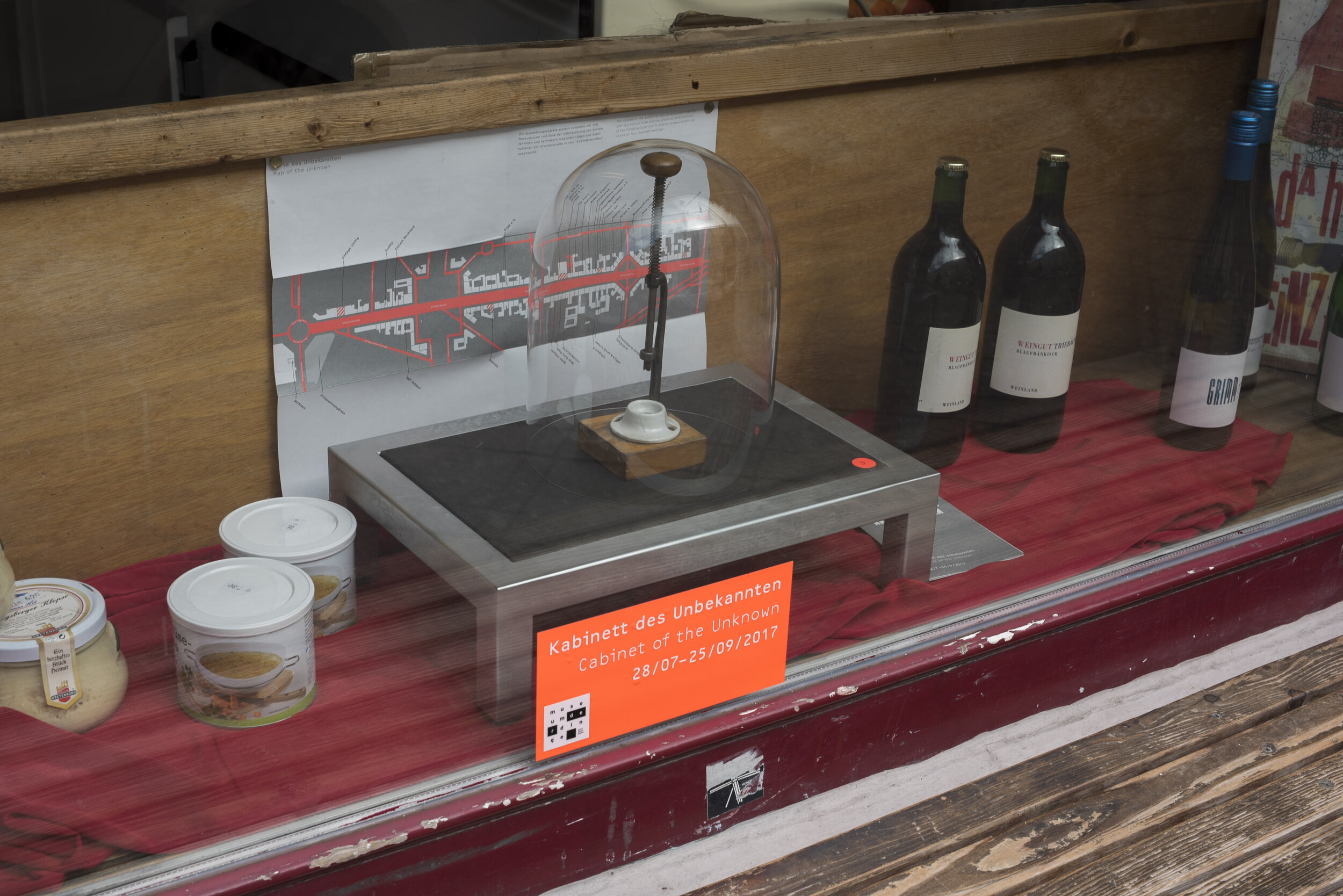

THE CABINET OF THE UNKNOWN

Werkbundarchiv- MUSEUM DER DINGE/ museum of things, berlin

28 jul – 25 sep 2017

The Cabinet of the Unknown is funded by the International Museum Fellowship Programme of the German Federal Cultural Foundation/ Kulturstiftung des Bundes.

“Eyes of the Skin” is a video that has been created in reference to Juhani Pallasmaa’s book under the same title, a book that served as the backbone of this participatory project. Focusing on methods of knowing and perception, the video has been realised with two visually impaired project participants.

by Ece Pazarbaşı

Camera and Editing: Alexander Gheorghiu

in collaboration with Die Imaginäre Manufaktur DIM 26 / USE, Union Sozialer Einrichtungen

PUBLIC PROGRAMME

1. „Cabinet Meetings“

During the following gatherings with the participants from the Oranienstrasse, the unknown objects were complied and the unknown locations/people selected:

First Cabinet Meeting – 16.05.2017

with: Cathrin Ebner, Akarsu e. V., Oranienstraße 25; Laurent Vivien, Bateau Ivre, Oranienstraße 18; Claudia Klemm, Buchhandlung Mondlicht, Oranienstraße 14; Thorsten Willenbrock, Kisch & Co., Oranienstraße 25; Ay ̧se & Atilla Temelta ̧s, Hong Kong Shop, Oranienstraße 180; Nina Weniger & Michael Wießler, Modern Graphics Buchhandel, Oranienstraße 22.

Second Cabinet Meeting – 01.06.2017

with: Naciye & Elliott Stein, Chocolateria Sünde, Oranienstraße 194; Marita Tenberg & Patrizia Schröter-Oduntan, Fadeninsel, Oranienstraße 23; Gisela Deutschmann, Lebensmittel Hillmann, Oranienstraße 20; Svenja Nette & Matthias Wilkens, Prinzessinnengärten, Prinzen- straße 35–38; Hans Meiners, Propolis Farben, Oranienstraße 19a; Yasin Müjdeci, Voo Store, Oranienstraße 24.

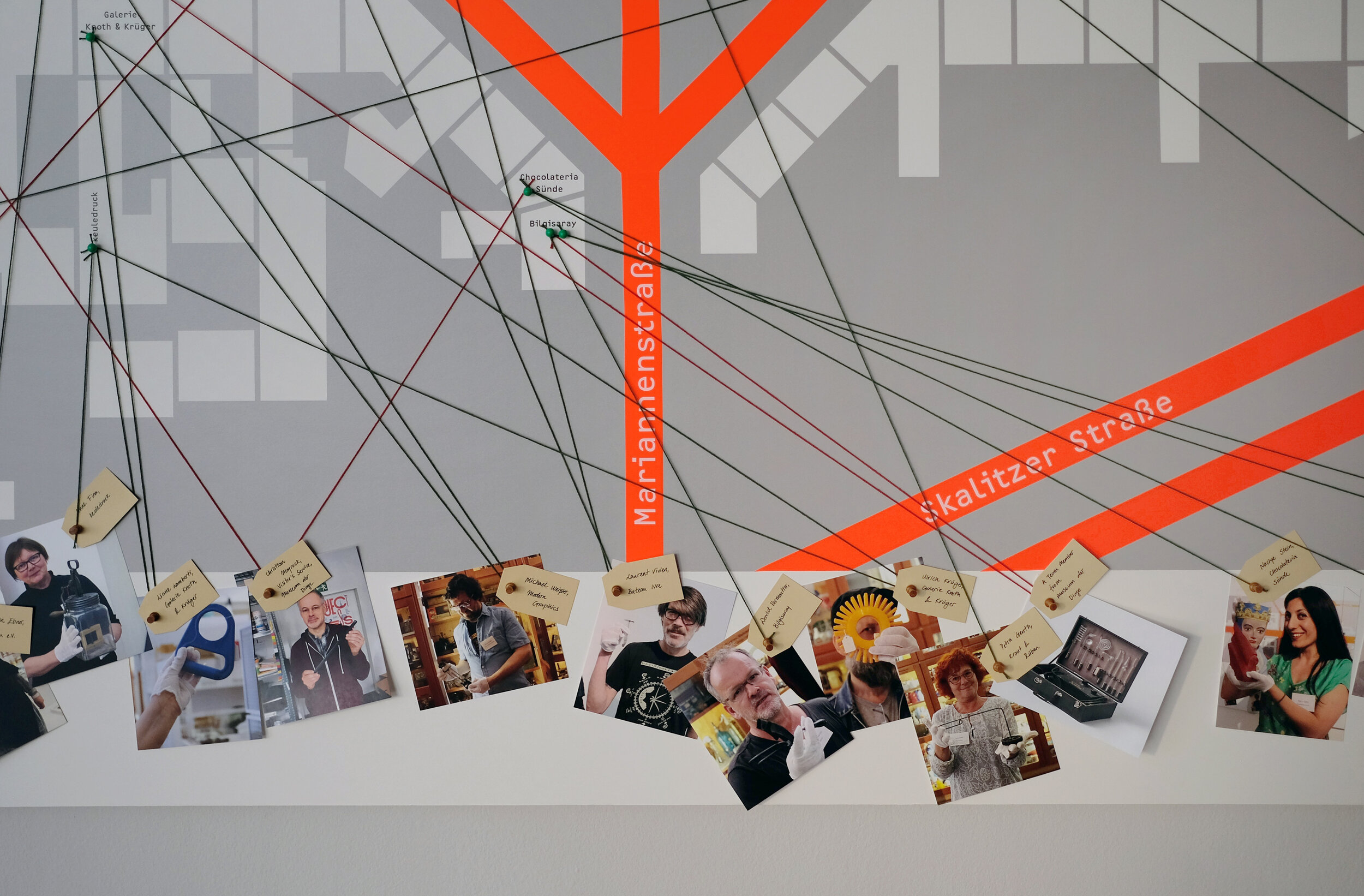

Third Cabinet Meeting – 13.06.2017

with: Marie & David Permantier, Benjamin Titze, Bilgisaray, Oranienstraße 194; Sophia Hannß, Collect Boutique, Oranienstraße 44; Frank Schönfeld & Tore Kempf, DIM 26/USE, Oranienstraße 26; Alice Luda, Franken Bar, Oranienstraße 19a; Ulrich Krüger & Liane Lamberti, Galerie Knoth & Krüger, Oranienstraße 188; Isabella Bauknecht & Gabriele Hilsberg, KinderMusikTheater e. V., Oranienstraße 19a; Hanna Burckhardt, Sarah Mohs & Hans Boes, Prinzessinnengärten, Prinzenstraße 35–38; Karin Erb, Rote Lippen Naturkosmetik, Oranienstraße 12; Charlotte Bastian, Scotty e. V., Oranienstraße 46; Gerd Gaumann, Zentralrad, Oranienstraße 20–21; Lisa Wiedemuth, Quartiermeister, Oranienstraße 183.

Fourth Cabinet Meeting – 27.06.2017

with: Matthias Bischoff, 360° Outdoor, Oranienstraße 164; Maria Leister, Anaveda, Oranienstraße 169; Selim Adanur, Coiffeur Selim, Oranienstraße 179; David Strempel, Coretex ecords, Oranienstraße 3; Anne Fina, keuledruck, Oranienstraße 188; Hans Hartnack, KIgA e. V., Oranienstraße 34; Petra Genth, Britta Mielenz & Annette Reiß, Kraut & Rüben, Oranienstraße 15; Lilian Engelmann, nGbK, Oranienstraße 25; Ute Meiler & Peter Althammer, Vintage Living, Oranienstraße 53; Felix Neuhaus, Werkhaus, Oranienstraße 45.

2. „The Unknown Dinner“ – 06.09.2017

The participants (i. e. Cabinet Members) were invited to the “Unknown Dinner.” Just like the exhibition was constituted with the unknown inputs, the Dinner was set up in the same way with five ingredients. Five “Cabinet Members” are selected to name an “unknown ingredient” that our amazing artist cooks, Sandra Teitge and Franziska Pierwoss used while preparing the dinner. The ingredients and the menu were as follows:

Cucumber with Tamarind (as chosen by Alice Luda, Franken Bar) & Dahlia “Arabian Night” (as chosen by Matthias Wilkens, Prinzessinnengärten)

Fish (as chosen by Selim Adanur, Coiffeur Selim) & Blue Potato Chips (as chosen Annette Reiß, Kraut & Rüben) Hoary Cress (Lepidium draba) (as chosen by Matthias Wilkens, Prinzessinnengärten)

Buckwheat (as chosen by Petra Genth, Kraut & Rüben) Risotto with Caramelised Onions, Mushrooms & Alpine Sorrel (Oxyria digyna) (as chosen by Matthias Wilkens, Prinzessinnengärten)

Turmeric (as chosen by Naciye Stein, Chocolateria Sünde) Parfait & Cocoa (as chosen by Naciye Stein, Chocolateria Sünde) Beans Waffle.

3. Talks and Discussions

All About the Berlin Key – Talk – 21.09.2017

Daniel Kannengießer, head of Kerfin & Co., was invited for a talk about the “Berliner Key”. This two-winged key is the “key-object” of the exhibition. Kerfin & Co., originally located in Kreuzberg, received the patent for this locking system in 1912.

As the finissage, a comparative insight into a tradition of presenting unknown objects from the 18th century – the so-called “Cabinet d’Ignorance” of the Princely Collections of the Saxon Court – was granted. Moderated by Dr. Jonas Tinius, the conversation took place between Dr. Michael Korey and Ece Pazarbası.

if you would like to obtain the catalogue of the project, please contact WErkbundarchiv - museum der dinge.

THE CABINET OF THE UNKNOWN PROJECT was subject to curator Anna Mária Juhász’s master thesis at university of AMSTERDAM. you can read Juhász’s thesis HERE.

A particular object, among the whole museum collection, that had never revealed itself to the curator before, suddenly evoked interest and an insatiable curiosity... Why would one have a key with two identical blades that mirror each other, rather than the usual single blade? Why would one use it, and what for? If this key is for a door, which parties does this door connect?

After a long period of research that took place with locksmiths and long-term residents of Berlin, the answer was revealed: the Berliner Key! A prominent topic for contemporary philosopher Bruno Latour, the Berliner Key is a two-sided-key that was designed to make people to close and lock their main entrance doors. The key was produced to replace the concierge, whose job was to open the door all through the night to whoever rings the bell. Acting as a tool of power mechanism, the key granted permission for the door to be opened on both sides towards and away from two different vistas – standing for a series of binary divisions: inside and outside; the tenants and the owners; institutions and audiences; the known and the unknown.

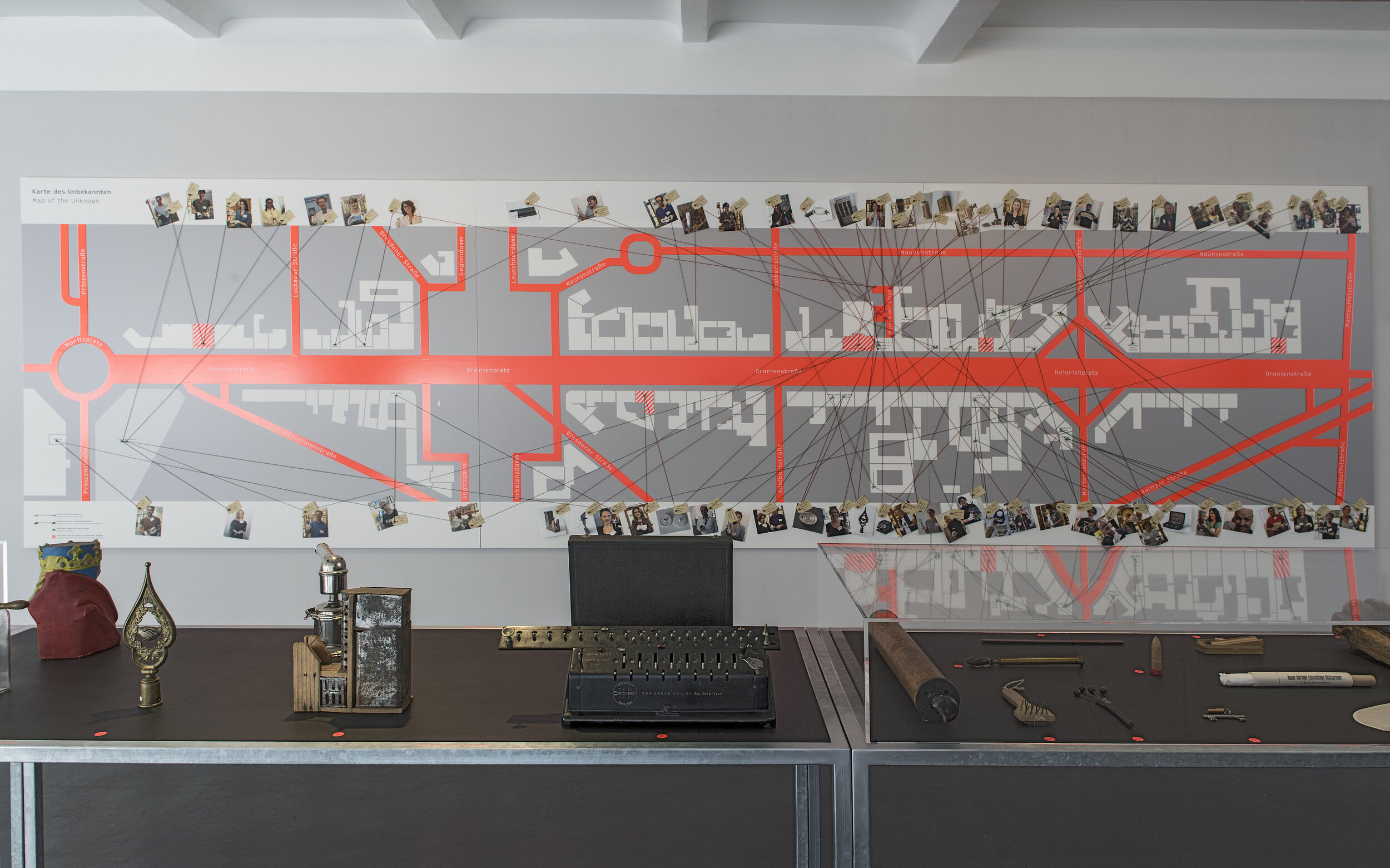

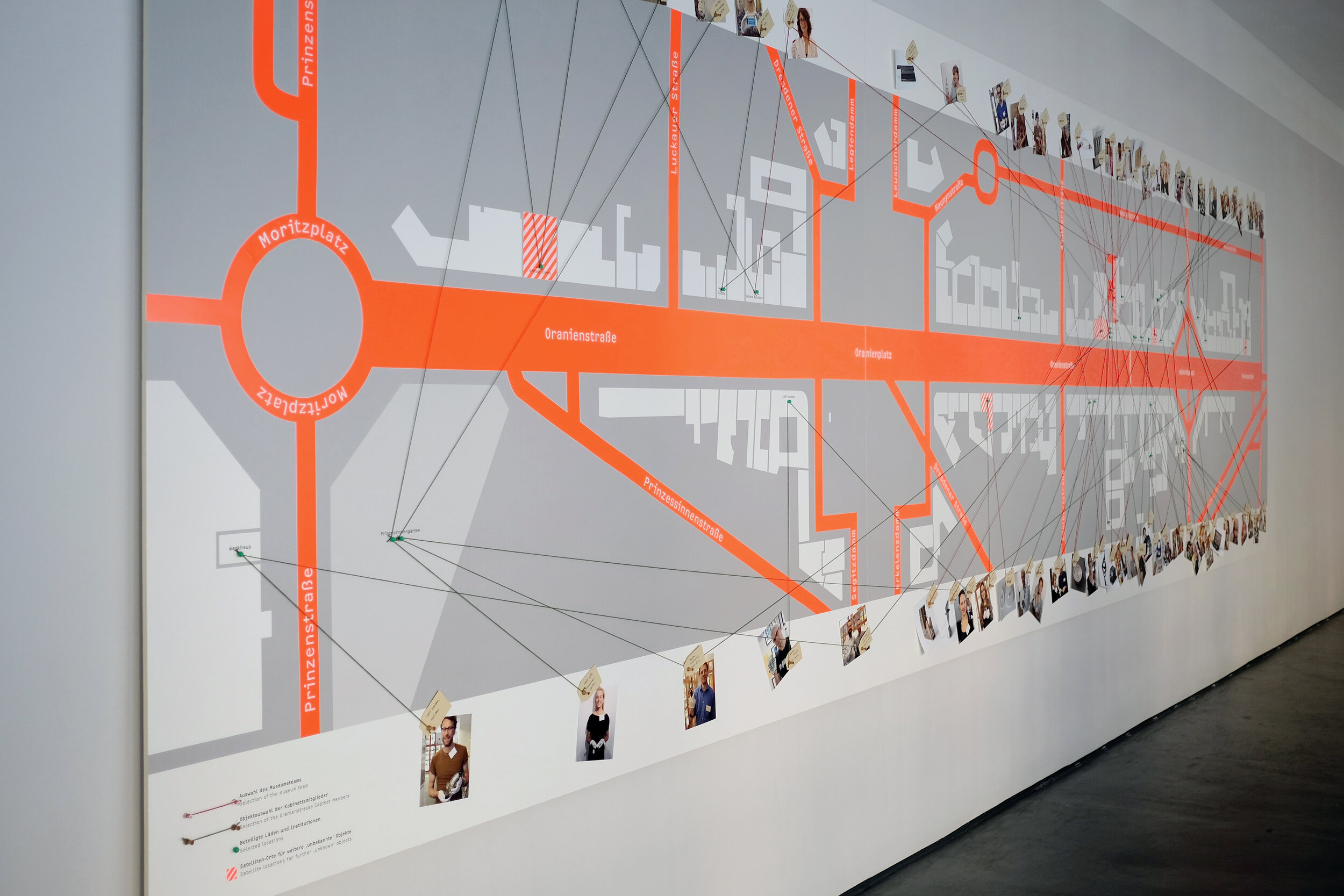

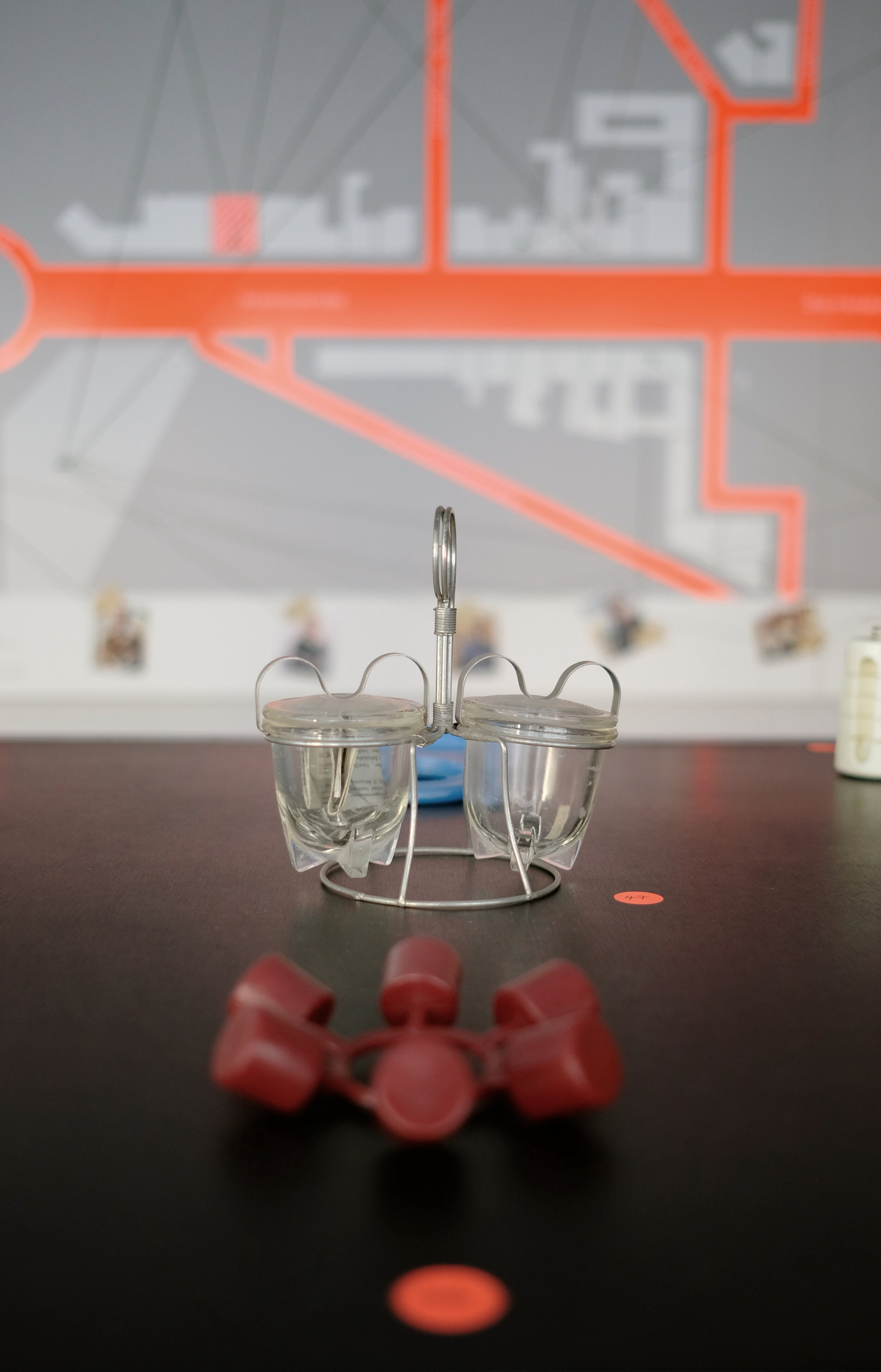

Taking the Berliner Key as the key object, the 10 “Cabinet of the Unknown” exhibition project dwells on the unknown through the processes of knowing and creating acquaintance. It pursues the goal to connect the known to the unknown by linking the museum in the backyard to the street in front, making the unknown of the museum (as well as the museum itself) knowable to its environment. It takes the museum into its centre and works with a peripheral approach through three main elements: the museum, the collection and its audience. With a ripple effect, the focus moves away from itself and expands towards a new audience from Oranienstrasse and beyond, while shifting the gaze from the focus to the periphery as well as shifting the attention from known objects that could be classified, to unknown objects that do not fit to any kind of taxonomy. In other words, the project gets involved with who is around the museum on Oranienstrasse and what is around the defined collection that remains as unknown at the museum. Working with (and within) the neighbourhood through unknown and undefined objects in the museum offers an alternative approach to create a connection with the local community as well as to bring a new understanding to the position of the museum itself in the audience context and re-evaluate the notion of institutionalisation of knowledge in the museum context.

The long tradition of museum practice calls for museums as institutions to provide knowledge. In traditional museology, knowledge is a commodity that a museum offers whereby the visitor entering the vicinity of the museum. The visitor has already accepted the correctness of the supplied information. Eventually, it is the duty of power mechanisms – that the conventional museums are part of – to act and to be perceived as the ultimate knowledge provider with an epistemological wisdom of everything.

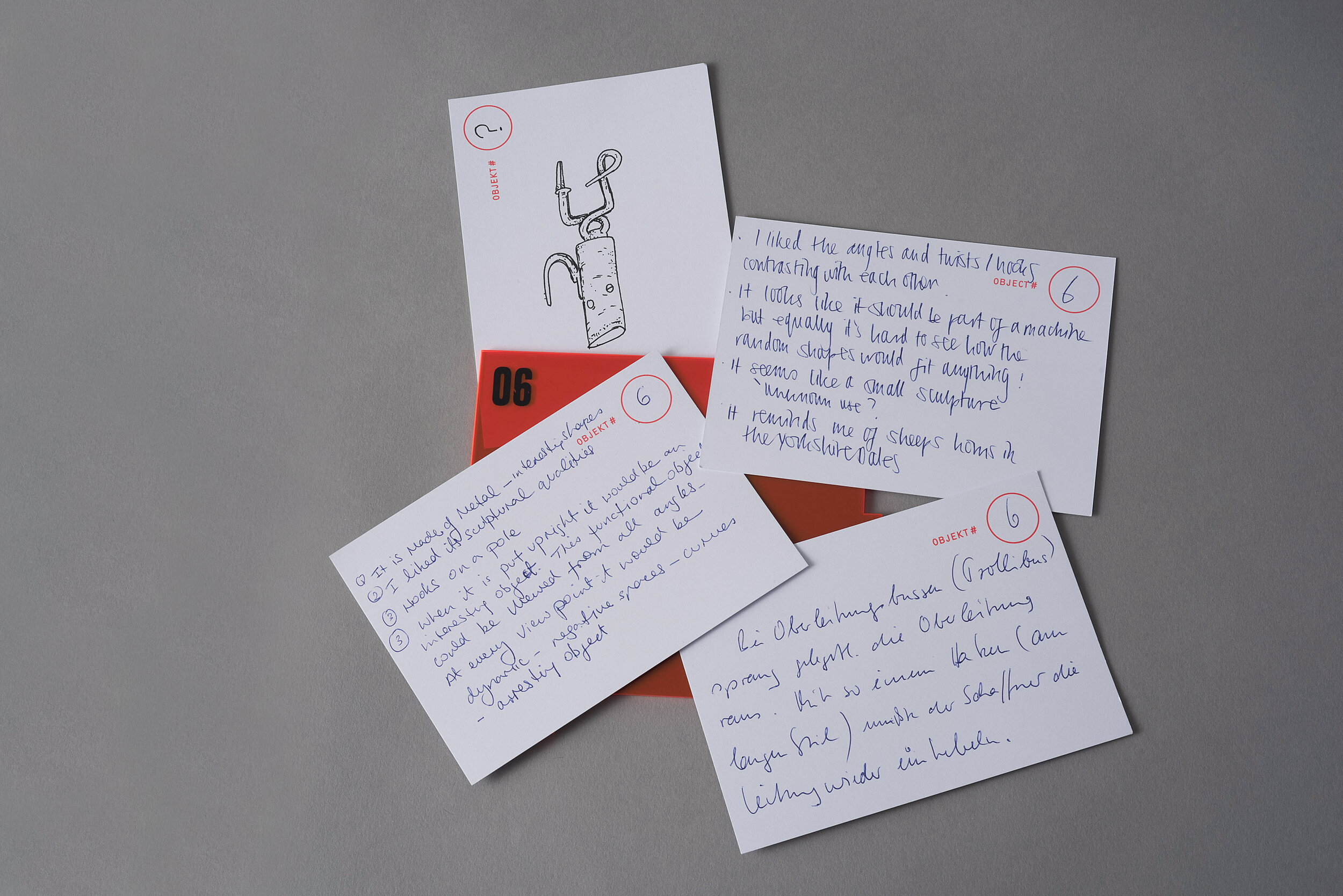

The project used an alternative trajectory to reach its goal. Within this perspective, it has invited Museum der Dinge – being already an untraditional museum in terms of taxonomy, curation and knowledge production – to expose its more fragile aspect, and share this with its community. The “Cabinet of the Unknown” incorporated the entire Museum Team as the starting point of the project, asking them which object in the museum’s own collection was unknown and alien to them. Acting somewhat unconventionally, the team then presented this vulnerability sourced in the lack of accurate knowledge on selected objects to their community. In addition to selecting an unknown object, the museum team was asked to name a place, person, organisation or a business – such as an unknown neighbour – that is either totally unknown to them or should be known more in depth.

For the second loop of the ripple, the project then invited the unknown neighbours selected by the museum team to work with the periphery of the collection; namely the unknown objects.

Did they have any idea about the museum team’s selection of the unknowns? What were their own unknown objects in the collection? Furthermore, how familiar was the museum to them in their own environment? And finally were there any interesting neighbours in their environment that they wished to connect with and this way to let them be invited by the museum for the third and the fourth loop of the project?

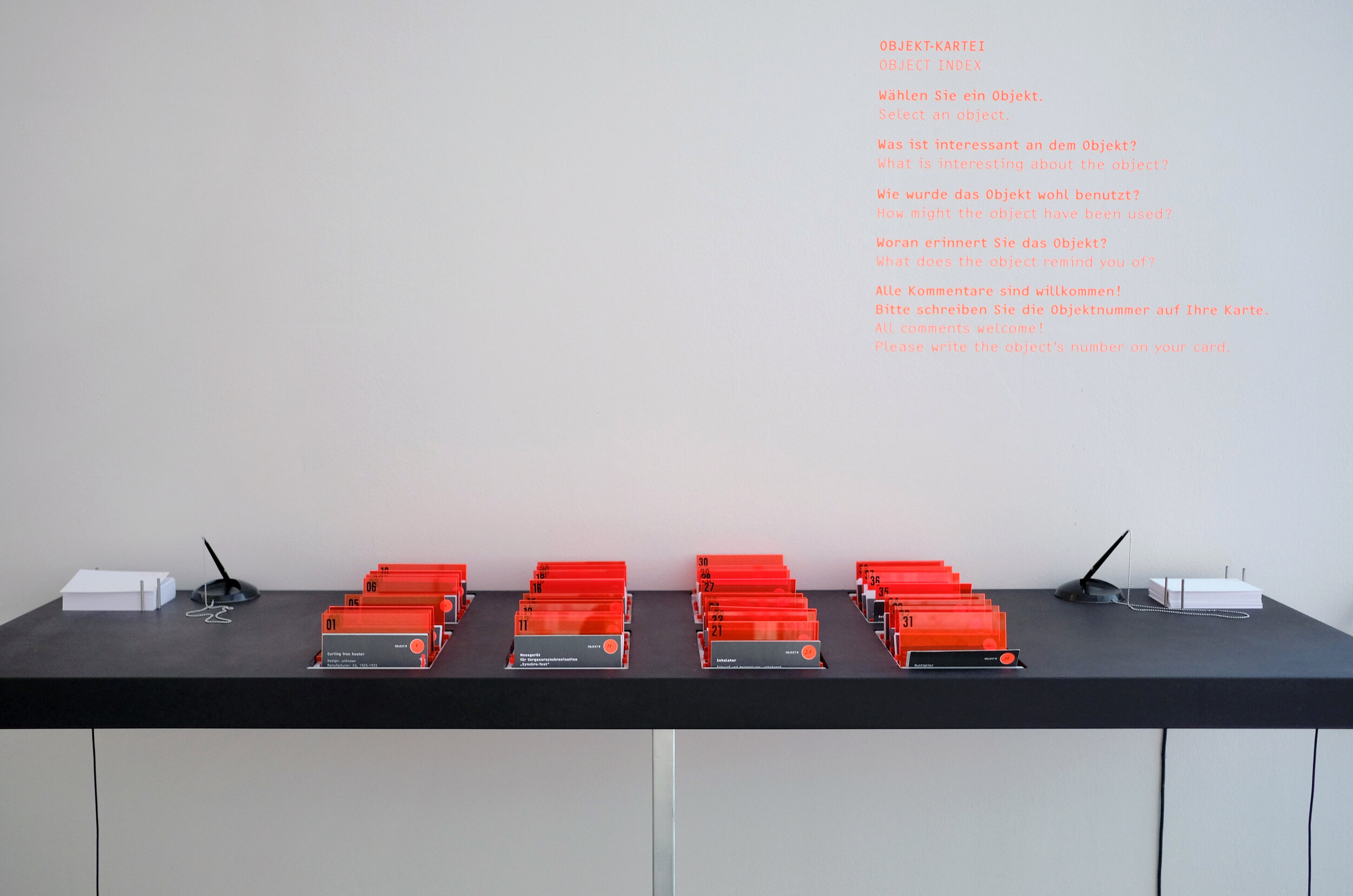

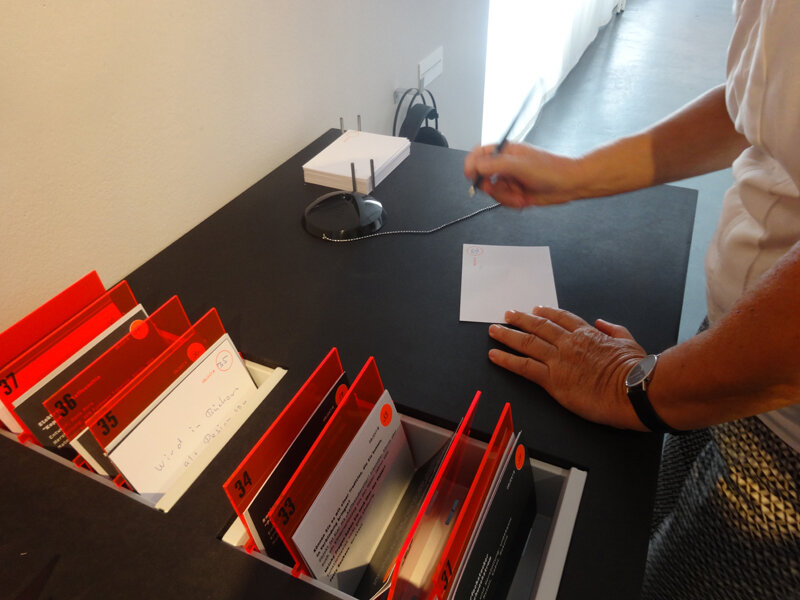

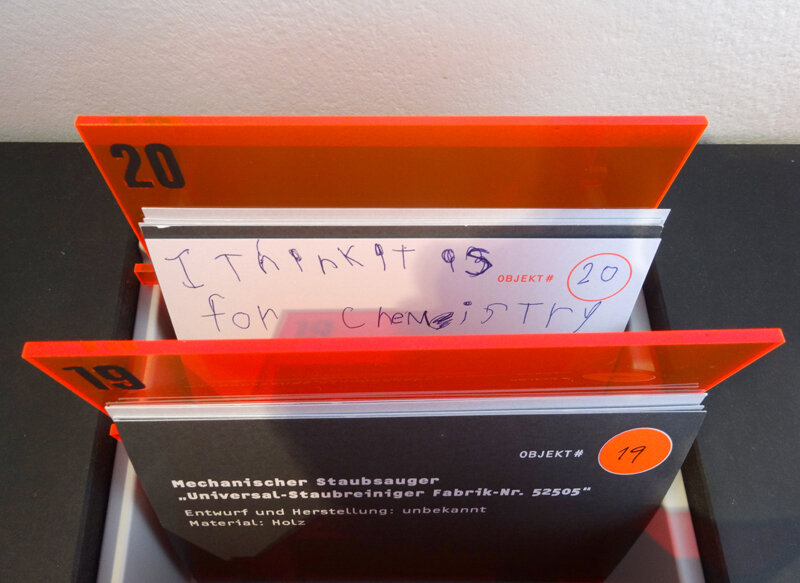

Working both with objects of periphery and the periphery of the museum’s geographical location, the project also uses a contextual connotation to “Cabinet d’Ignorance” that existed at Princely Collections of the Saxon court in Dresden back in the 1730s. The “Cabinet d’Ignorance” was created for those items that cannot be named or classified, and which have an “unknown nature, petrifactions, animals, monsters whose names and natures are not known” as London antiquarian John Milles states, “for which the visitors were invited to suggest identifications” (Bedini, 11).

The “Cabinet d’Ignorance” reflects views that are both for and against the desire for taxonomy in the traditional Western museology. It is a cabinet that adequately announces the fragility of the fact that some objects in the museum cannot be classified or to put it simply: be known. Nevertheless, the very act of doing this creates itself a taxonomy of unknown objects. Considering Museum der Dinge’s representation that is already more open than many other traditional institutions and following a format of cabinets of associations in its curatorial preference, it becomes clear that the motivation behind “Cabinet d’Ignorance” can still be seen as both contemporary and relevant. Additionally, by being open to visitor identifications and suggestions, it creates another chance to revisit the museological contexts with participatory behaviour, which supports communal inclusiveness both for the museum and its audience.

From this perspective, the project does not look at the objects that are usually within the focal point of the collection, but beyond those that are at the periphery. It does not bring the museum into focus, but its periphery situated on Oranienstrasse. Following Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa’s statement on architecture as the main participatory trajectory of the project: the “peripheral vision integrates us with space, while focused vision pushes us out of the space, making us mere spectators” (Pallasmaa, 13), the project incorporates the locational and communal periphery of the museum as well as its collection. It is an act of creating closer acquaintance through participation, rather than allowing the museum to remain as another commodity for inactive spectatorship. In-line with the project’s direction, Pallasmaa in his book Eyes of the Skin continues: “The defensive and unfocused gaze of our time, burdened by sensory overload, may eventually open up new realms of vision and thought, freed of the implicit desire of the eye for control and power. The loss of focus can liberate the eye from its historical patriarchal domination” (ibid.).

The curator’s unknown object

The Berliner Key is a two-sided-key that was created to impose people to close and lock the doors of the main gate opening to a common yard. Its particularity comes from the fact that it has two key blades (the part which activates the bolt), one at each end of the key, rather than the usual single blade. Right after unlocking the door, the key must be pushed through the keyhole and retrieved on the other side of the door only after it has been closed, and locked again. Invented by the Berliner locksmith Johannes Schweiger, since 1912, the Berliner Key is being produced by the Albert Kerfin & Co. Although this kind of lock and key is becoming less common, it is still in use in some tenement buildings of Berlin.

The interaction between the concierge (whose task was to open the door at night) and the tenants has ended when the property owner swapped the concierge with a key with two identical bits to streamline his/her building’s entry control mechanism. The key became the object that allows the tenant to his/her home only if s/he follows the rule of the key.

Bruno Latour, in his text “The Berlin Key or How To do Words With Things”, addresses this unique thing, a thing of its own that only existed in Berlin, as an object that dictates and inducts a rule. The key – even only by sitting in its owner’s pocket – reflects the mentality that produced a technology that stands for the control mechanism. Berliner Key’s task and what it dictates is inscribed in its very nature.

“The Berlin key, the door, and the concierge are engaged in a bitter struggle for control and access. Shall we say that the social relations between tenants and owners, or inhabitants and thieves, or inhabitants and delivery people, or co-owners and concierges, are mediated by the key, the lock, and the Prussian Locksmith?” states Bruno Latour in his piece (Latour, 18). The key indeed creates many control mechanisms mainly between the ones who live in flats and those who can afford to buy a building. Just as access and control are reflected in governmental bodies’ control of other keys – visas and passports – and permissions for others mirror a stand in foreign politics; just as alarm systems in shops and malls reduce the need for on site human security and walls erected between people indicate the state of interior politics, as approval stamps on documents other related institutions, so too does the Berliner Key stand for the mechanism of power within a single contained community of neighbours.

Works cited

Bedini, Silvio A.. “The evolution of science museums.” Technology and Culture 6/1 (1965), pp. 1–29.

Pallasmaa, Juhani. The eyes of the skin: architecture and the senses. Chichester: Wiley, 2014.

Latour, Bruno. “The Berlin Key or How to Do Words with Things.” Matter, Materiality and Modern Culture. Ed. P. M. Graves-Brown. London: Routledge, 1991. pp 10–21.

![Sliding vehicle “Arschrutsche” [“ass slide”] ☛ Peter Althammer Photo: Armin Herrmann](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e97821275d49f2a3ca625bb/1610811874683-H9HON5YEUC4I3UVC0S7I/_NIK4129.JPG)